by Charlotte M. Crabtree and Bart Mullin, AAA

(Originally printed in the Chubb Insurance Newsletter)

The words “Southern silver” can conjure the romantic image of a delicate Southern belle gathering up and burying her family’s most treasured silver heirlooms only moments before the Yankees descend upon the plantation. Perhaps the romance of such an image can be credited with the recent explosion in prices in the Southern silver collector marketplace, but this article helps us move beyond the romantic, to a better understanding of the trend. It will help those new to this collecting area by exploring what defines Southern coin silver and what determines its value.

To understand Southern silver it is necessary, first, to define coin silver. Most solid silver articles made in America prior to 1870 are of the “coin” standard, which averages approximately 900 parts pure silver per 1000. The term “coin silver” is derived from the very early practice of melting down coinage and refashioning the metal into wares of silver. Numerous silversmiths in both Northern and Southern U.S. cities hand crafted pieces of flatware and hollowware, usually marking them with their initials, or a combination of their initials and surnames. These marks appear either impressed into the metal’s surface with the letters in relief, or stamped in a manner that recessed them into the metal’s surface (known as incising). The impressed mark is the older, though the two were used simultaneously beginning around 1840. By 1860 virtually all silver marks were incised. Occasionally, secondary marks, also called pseudo or trade marks, may be found on Southern silver: a man’s head reminiscent of the sovereign’s head on English silver, single letters of the alphabet, a bird, etc. These marks were used by silver sellers to promote their wares, if not in imitation, then often reminiscent of the marks on quality silver from England and the Continent.

Defining Southern silver entails examining the region’s history as well as geography. The Confederate States of America were Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Tennessee, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, and Arkansas. Kentucky and Maryland were border states, and both had great internal conflicts over the subject of secession. While the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) located in Winston-Salem, NC, recognizes articles made in Kentucky and Maryland as being Southern, most collectors of Southern coin silver exclude Maryland. One theory for the exclusion cites the clearly “Northern” city of Philadelphia’s strong stylistic influence on Maryland silversmiths. Whatever the case, Southern silver’s chief trait is its scarcity.

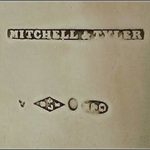

Example of impressed marks on the bottom of a coin silver creamer, bearing the marks of Mitchell & Tyler of VA and William Gale & Son of NY. Private collection. Image by Charlotte Crabtree

Several factors account for the scattered existence of Southern silver, and one is an examination of statistics. The South simply had fewer silversmiths in operation than the North. The publication New York State Silversmiths by The Darling Foundation reveals there were a little over 283 silversmiths and jewelers working in NY between 1800-1810, while Charleston, the South’s prosperous center during that time, supported only 79. Additionally, the recyclable nature of silver surely lead to a number of Southern-made pieces being melted down and designed into more fashionable forms. The South also had its share of natural disasters, such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and fires to take their toll on its wares. And, we know that wars “liberated” much Southern silver. Milby Burton, in his book South Carolina Silversmiths, 1670 to 1860, talks about the estimated loot, valued at 300,000 pounds sterling, taken from Charleston by the British during the War for Independence. Burton continues by recounting a disturbing letter found near Camden, SC, from Union Lieutenant Thomas J. Myers. Myers wrote home stating:

“We have had a glorious time in this State. Unrestricted license to burn and plunder was the order of the day. The chivalry [another word for landed gentry] have been stripped of most of their valuables. Gold watches, silver pitchers, cups, spoons, forks, &c., &c. are as common in camp as blackberries… We took gold and silver enough from the d—d rebels to have redeemed their infernal currency twice over.”

On a brighter note, however, we know of a Southern family that documents being reunited with a silver cup decades after its possible acquisition during the “Great Unpleasantness.” They credit the diligence of one Union officer’s descendant interpreting the engraving and markings on the piece’s body for its safe return.

A closer examination of the secondary marks mentioned earlier reveals a complex and highly debated issue of retailer versus maker. After the turn of the 19th century and the integration of the industrial revolution, some Southern makers found it more profitable to import wares made by large Northern manufacturers. These Southern retailers often marked the pieces with their own names and offered them to their communities. This explains why engraved inscriptions to prominent Southern families and institutions occur on articles made by firms like Gorham of Providence, and Theodore Evans & Co. of New York. The impressed mark usually denotes the maker, while the incised mark is likely the retailer. In the case of two impressed marks, a study into the size, workforce, and location of both firms can identify the roles of each. While purist collectors strive for pieces actually made in the South, Southern related pieces also highlight the roll of the Southern retailer. Firms like Hyde & Goodrich of New Orleans and James Conning of Mobile provided a vital link to other markets and styles. As a result, the market remains quite accepting of Southern-related pieces.

With a definition of Southern coin silver and an explanation of its scarcity in hand, four criteria now play a significant role in establishing its value: condition, craftsmanship, rarity and provenance. What do we mean by condition? The formula might be expressed as a piece’s proximity to its original condition plus its age. Age and regular use result in patina, and these tiny “scratches” on the surface give a muted, soft luster to a piece. In some hollowware, the presence of firescale is most exciting. Occurring during the manufacturing process, it resembles a bluish-gray or copper film that cannot be removed by ordinary polishing. Technically, copper oxides form and then penetrate the surface of the metal during the annealing process. By the last quarter of the 19th century, changes in the manufacturing of silver eliminated this interesting feature.

Example of firescale on the side of a coin silver creamer bearing the marks of Mitchell & Tyler of VA and William Gale & Son of NY. Private collection.

Connoisseurs of Southern coin consider certain names like A.E. Warner of Baltimore and Alexander Petrie of Charleston synonymous with superior craftsmanship. While superior craftsmanship includes well defined ornamentation and minimal delamination (the flaking of the metal when not properly annealed), the thickness and weight of the metal used might reflect more on the patron than on the craftsman. How much a patron was willing to invest in a piece, after all, governed the amount of material used by the silversmith.

As location is the golden rule of real estate, some scholars consider rarity to be the golden rule of all coin silver. The supply simply cannot keep up with the demand. Most astute collectors will overlook poor condition if a piece’s form, mark and/or characteristic were previously unknown. A pattern called “Mulberry”, with wide, ribbed oval leaves and small berries, is specifically indigenous to Charleston and provides one example of a rare and desirable Southern form.

American coin silver cup presented by William R. Huntt, SC’s Secretary of State, to an unknown recipient in 1859, and bears the mark of Radcliffe and Guignard of Columbia, SC. Private collection. Image by Charlotte Crabtree

The story of a cup found in a Charleston antique mall beautifully illustrates the importance of provenance. The bottom of the cup was marked by a Columbia, SC firm, Radcliffe and Guignard, working circa 1855. But a twenty hour investigation in the library to identify the names engraved on the cup’s body, “Wm. R. Huntt to S.M.B, 18th Feby 1859” brought nothing more than eyestrain. The big break finally came at a small private library. William Richardson Huntt was South Carolina’s Secretary of State when the Civil War broke out, and anticipating that Sherman’s troops would burn and pillage the state capital, he gathered up 90 boxes of important SC documents and artifacts, including the Ordinance of Secession and the state seal, and evaded Union troops with them until the end of the war. The cup, now linked to an important SC statesman, gained new historical relevance and doubled in value.

So where is the market for Southern silver headed? If auction results of the last half decade continue, the answer is towards higher prices. No one yet knows the scope of the losses of Southern silver that occurred from Hurricane Katrina, and to decorative arts there in general. So far these have yet to be reflected in the market place, but shortages may yet be coming.

While a more in-depth discussion of the topics above could provide more facts, it would not convey the virtues of Southern coin silver at its best: gentility, tenacity and romance. It is the quest and passion to obtain these qualities that inspires Southern coin collectors for a lifetime.

Keys to successfully collecting and investing in Southern silver include the following:

Analyze condition, craftsmanship, rarity and provenance.

Invest in and study books specifically dealing with each state’s craftsmen. They provide so much more knowledge than the general books dealing with all craftsmen.

Never forget to ask about the source of a piece.

Use a polish designed especially for silver, such as Gorham, Goddards, or Hagerty’s. Stay away from dips and polishes designed for all metals.

Make sure the form is consistent with the time frame.

Buy the very best quality you can afford. Always choose quality over quantity.

Frequent museums with notable Southern silver collections.

Avoid buffing, if possible.

If restoration and conservation are necessary, seek a silversmith whose techniques and approach are consistent with those of leading museum conservators.

Every few years, have a certified appraiser evaluate your collection and note any market changes.

About the Authors

Bart Mullin, AAA is a certified member of the Appraiser’s Association of America and Vice-President of the South Carolina Silver Society. He founded Bart Mullin Appraisal Company in 1994 and is a principle in Read & Mullin, LLC.

Charlotte M. Crabtree, along with her husband Al Crabtree, owns The Silver Vault of Charleston and The Brass & Silver Workshop. She has been studying decorative arts for 20 years.